Progressive Jackpot

Game Terpopuler

Promosi

Masuk Ke Dunia QQSLOT Autentik Melalui Link Alternatif Resmi: Kepuasan dan Kemenangan Tanpa Batas Menanti Anda

Kenalan Yuk dengan QQSLOT dan Penawarannya yang Top Banget!

Halo bro sis! Welcome to QQSLOT, pintu masuk lo ke dunia game online yang menjamin keseruan dan kemenangan yang gede banget. Sebagai tempat judi online yang paling hits, QQSLOT punya macem-macem game yang dirancang khusus buat memenuhi selera beragam pemain kita. Mulai dari slot yang bikin adrenalin lo naik, sampe e-games yang seru abis, semua disajikan dengan keamanan dan keaslian yang top.

Qqslot Situs link daftar dan link login yang memiliki server terbaik sehingga pada tahun ini sebagai situs tergacor yang selalu ada di Asia sampai sekarang ini. Memberikan kemenangan setiap hari nya kepada para member baru tanpa harus terapkan pola apapun.

Gimana Sih QQSLOT Jamin Keaslian dan Keamanan Game?

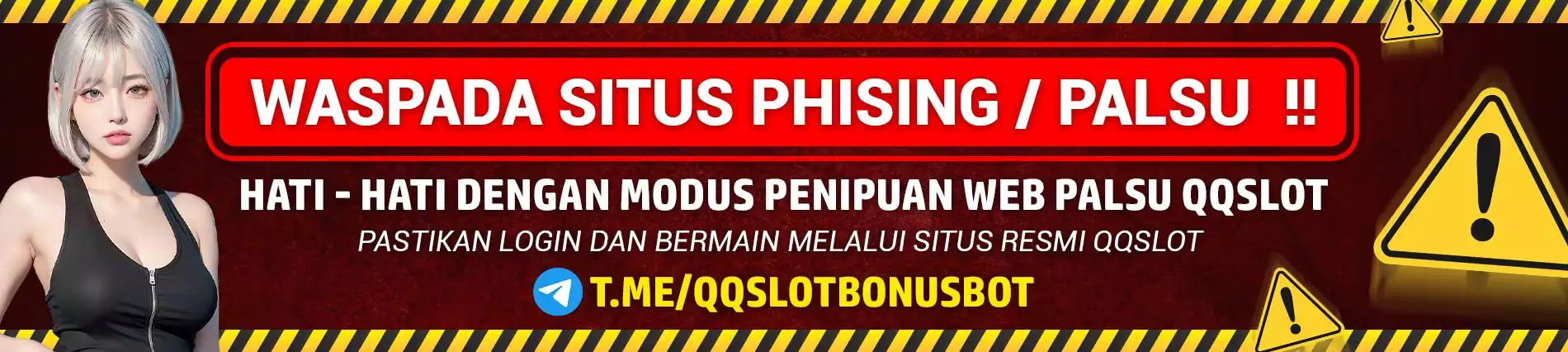

Di QQSLOT, keamanan itu prioritas utama kita. Platform kita dilengkapi dengan teknologi keamanan paling canggih buat memastikan kenyamanan dan keamanan bermain kamu. Lo bakal main dengan tenang karena kita cuma pake link resmi buat akses, yang melindungi dari bahaya phishing atau scam.

Cek Yuk, Berbagai Game yang Bisa Lo Mainin di QQSLOT

QQSLOT menawarkan macem-macem permainan, termasuk:

- Slot Games: Nikmati berbagai slot dengan tema unik dan gameplay yang keren.

- E-Games: Rasakan game elektronik terbaru yang mix antara tradisional dan modern.

- Table Games: Mainkan game klasik kasino seperti poker, blackjack, dan roulette.

Jelajahi Pilihan Game Seru di QQSLOT

Platform kita punya game dari developer top seperti Pragmatic Play dan Habanero di platform qqslot online yang menjamin grafis berkualitas dan pengalaman yang immersive.

Slot Games yang Wajib Dicoba di QQSLOT

Coba deh game di platform qqslot populer seperti "Starburst" atau "Book of Dead" yang punya grafis mantap dan tema yang menarik.

E-Games Eksklusif dan Fitur-fitur Menariknya

Temukan e-games eksklusif yang hanya ada di QQSLOT, dirancang buat memanjakan dan menghibur setiap pemain.

Tips Maximalkan Peluang Menang Lo di QQSLOT

Pelajari strategi buat meningkatkan permainan lo dan tingkatin kesempatan lo buat dapetin jackpot besar di QQSLOT.

Pentingnya Pake Link Alternatif Resmi Buat Akses QQSLOT

Menggunakan link resmi itu penting banget buat memastikan lo masuk ke platform QQSLOT yang asli, jadi data lo aman dan pengalaman bermain lo lancar.

Kenapa Sih Link Resmi Itu Lebih Aman?

Link resmi itu sudah diverifikasi dan dijamin aman, menghilangkan risiko phishing dan ancaman online lainnya.

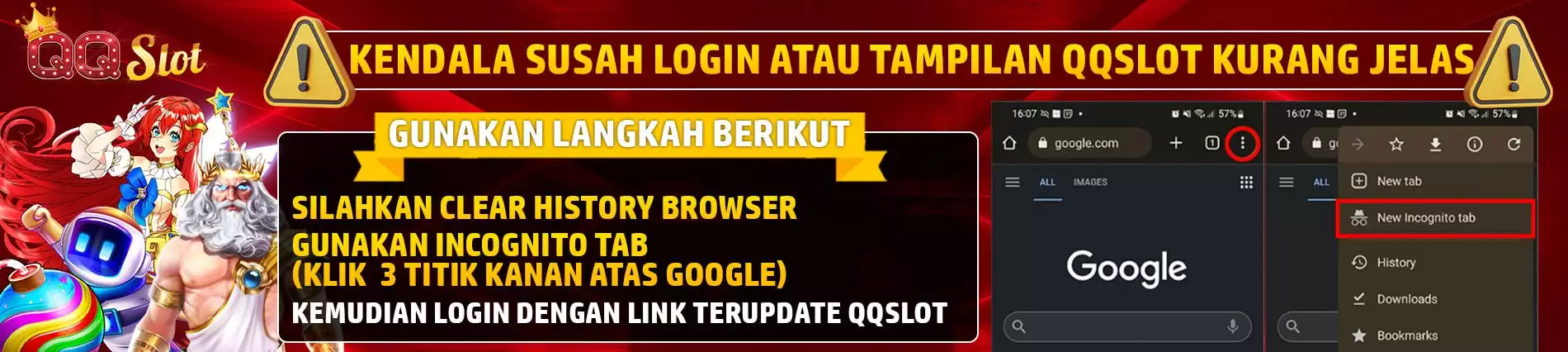

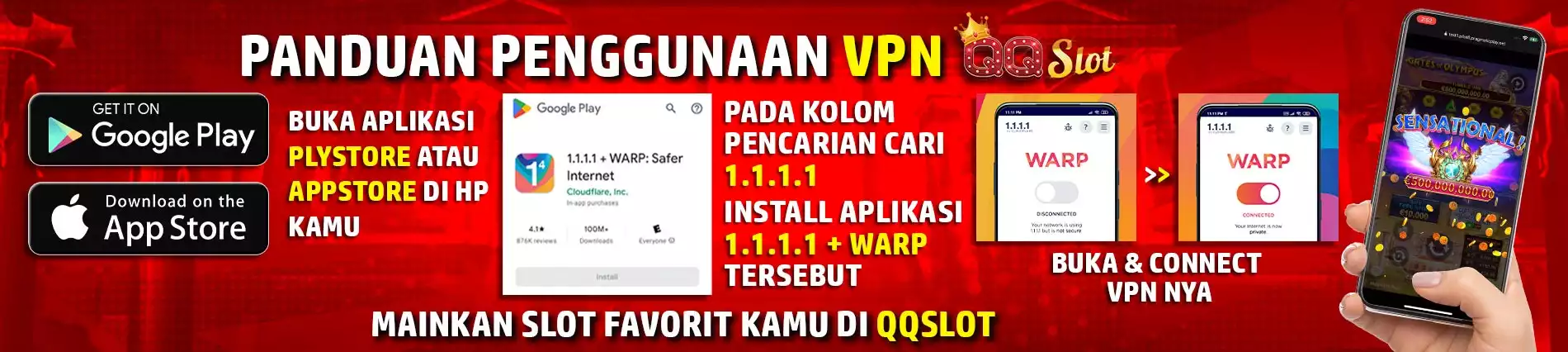

Panduan Gampang Akses QQSLOT lewat Link Resmi

Ikuti panduan simpel dari kita buat akses secara aman ke semua game dan fitur yang ditawarkan QQSLOT.

Komitmen QQSLOT Buat Kepuasan dan Keamanan Pengguna

Kita selalu utamakan kepuasan dan keamanan pengguna, jadi pengalaman bermain lo dijamin transparan dan aman.

Proses Transaksi yang Transparan di QQSLOT

Mengerti deh proses transaksi kita yang simpel, dirancang buat transaksi finansial yang cepat dan jelas.

Layanan Pelanggan dan Dukungan di QQSLOT

Tim support kita yang ramah dan profesional siap membantu lo dengan segala pertanyaan atau masalah yang mungkin muncul.

Cara Hubungi Dukungan dan Dapatkan Bantuan

Pelajari cara-cara terbaik buat kontak tim support qqslot online asli kita buat bantuan yang cepat dan efektif.

Tips Buat Pengalaman Bermain QQSLOT yang Lancar

Dapetin tips-tips praktis buat meningkatkan pengalaman bermain lo di QQSLOT.

Kesimpulan

QQSLOT itu kayak mercusuar buat fun, keamanan, dan peluang menang yang gede. Dengan link yang aman dan desain yang fokus pada user, tiap kunjungan lo bakalan terasa kayak masuk ke dunia kesempatan yang luas. Ayo gabung sekarang dan mulai petualangan lo untuk menang besar!

FAQ

- Gimana caranya biar pasti pake link resmi QQSLOT?

- Apa aja sih permainan paling ngetop di QQSLOT?

- Gimana cara hubungi customer service kalo ada masalah?

- Apa aja keuntungan main di QQSLOT?

- Gimana QQSLOT jamin keamanan permainannya?

- Bisa main di QQSLOT dari perangkat apa aja gak?

Nah, itu dia ulasan mengenai situs qqslot yang asli dimana kalian bisa bermain dengan tenang dan aman karena kami menjamin semuanya.

Sistem Pembayaran

Perhatian.

KLAIM BONUS 100% DENGAN TURNOVER SUPER KECIL DISINI

============================================

DEPOSIT INSTAN QRID PROSES DEPOSIT HANYA 3 DETIK

Pertama di Indonesia Proses Deposit Tercepat 3 Detik Auto Gacor, Tanpa Potongan / Biaya

Tersedia Untuk Semua Bank lokal - E-wallet

Dari Pada Tunggu Lama Yuk QRID Saja.

============================================

Link ALTERANTIF : https://qqslotfix.com

Link AMPLOP : https://qqslotangpao.com/

Link DEPO STREAK : https://qqslotevent.net/depositstreak

============================================

Deposit Lewat Mesin EDC Akan Di Proses Setelah 1 x 24 Jam

Pastikan rekening tujuan sebelum mengirim, jika ada kesalahan itu bukan tanggung jawab kami.

Formulir Login

VERIFICATION NOTICE

- I am agree to qqslot's term and condition.

- I am over the age of 21 and will comply with the above statement.

By entering this website, you acknowledge and confirm: